Laos | The Secret War

After a six month delay and lots of preparations, my friend, Al Willner, and I were set to leave on our next adventure. This time the theme of our trips would be the CIA Secret War in Laos and the Vietnam War (or American War as it is called in Vietnam).

Coming along with us for the Laos portion and to Hanoi would be my daughter, Nabra. She had just had a very successful opening of her play "Memory Lane is a Desert Road" - I plan to do a blog on that experience as she put me down as co-playwright and it was a pretty intense and nerve wracking adventure of its own.

We all met up in Los Angeles and flew to Vientiane arriving late at night on the second day of Bee Ma Lao (the Lao New Year).

Roving bands of celebrants armed with water pistols celebrate the Lao New Year and Water Festival | Vientiane

As we proceeded into town, our hotel had cautioned us that it may take some time because of the New Year celebrations. The weather was warm and humid and all seemed pretty quiet until we entered the city. The taxi driver rolled up the windows and soon we were stuck in heavy traffic as we passed by bars and night clubs - pulsating with techno tunes and drenched people with water hoses and white face paint.

Day One | Vientiane

We met up for breakfast with my sister Juliet who had been on a tour through Cambodia and Vietnam. She had already been in Laos for a few days and had toured Luang Prabang and Vang Vieng and loved it.

Though Al had try to make arrangements for our trips in advance, visiting remote CIA Secret War sites had proved challenging. Initially we had planned to visit the huge CIA airfield at Long Tieng, but the adventure tour outfit Tiger Trails could not guarantee the road there would be passable. So after some research, Al had come up with an alternative site - the battle at Lima Site 85 in the remote northeastern mountains only a few miles from Vietnam.

After breakfast we headed out towards the Laos Tourist Information Center in hopes of arranging transportation and accommodations for our stay in Sam Nuea the next day. It was hot and humid and the streets were deserted after late night partying. Most everything was closed and so was the tourist office. So we would now just need to wing it when we arrived in Sam Nuea.

Nabra pours water over a reclining Buddha which is done to seek merit and blessings | The Lao News Agency has seen better times | Al views murals outside the American Center | Vientiane

Lao New Year ritual at Buddhist Temple | 30 sec video | Vientiane

It took some time and negotiating as there were few people or vehicles in the streets, but we arranged for an all day tuk-tuk tour with driver, Phocon.

First stop was the eclectic Buddha Park some 22 kilometers away. As we were probably the only tourists making this trip in an open vehicle, we were the frequent target of Lao New Year celebrants who had not only water hoses in hand, but had also set up inflated baby pools along side the road and with large containers would throw water - sometime colored - at us. It was actually a lot of fun and was a nice way to cool down.

Al, in the spirt of the New Year, savors a soaking | Vientiane | photo contribution by Al Willner

Just one of many water soakings | Lao New Year | 45 sec video | Vientiane

Scenes from the Wat Xieng Khouane Buddha Park |

Buddha and Hindu diety creature statues | the demon head entrance | Chinese visitors with matching Hawaiian shirts | reclining Buddha and prayer shrine | Nabra and a duck friend | on top of the three levels of life structure | Vientiane

The park was created by priest-shaman Luang Pu Bunleua in 1958. The reinforced concrete statues and structures integrates elements of Hinduism and Buddhism with Bunleua own spiritual concepts. In 1975, he fled across the border to Thailand fearing repercussions from the communist Pathet Lao that took over the country. He created another similar park a few kilometers away on the other-side of the border. The Laotian government now runs the Buddha Park as a tourist attraction and public park.

With most sites being closed because of the holiday, we still tried to see if the Kaysone Memorial where the CIA ran their Secret War for 11 years and where the leader of the Communist Lao People's Revolutionary Party and former Laotian President Kaysone Phomvihane lived from 1975 until his death in 1992. Though the gates were open and we could see it through the trees, the Laotian guard would not let us onto the grounds.

US built 1960s Kaysone Memorial and site of the CIA headquarters during the Secret War | Kaysone Phomvihane Museum | Vientiane

After meeting some French travelers who highly recommended the Vientiane Art Museum (it was open), we decided to check it out. Though it was an art museum practically the only art work other than some immense paintings were hundreds of very impressive wood sculptures.

Wood sculptures | Vientiane Art Museum

And some snaps from around town |

motorcyclists with Victory Monument in background - with was reportedly built with US-donated cement that was suppose to go to building an airport | monks | temple vendors | monks at at the ready to splash people as a symbol of cleansing and blessing | temple goers - one seemingly dressed as an NYPD police person | paying tribute by pouring water over Buddhas | a mister to keep people cool and as a blessing | Vientiane

For dinner, we decided to check out restaurants along the Mekong River and had to run the gauntlet of water ready celebrants and were soon soaking wet. On the way back I used other pedestrians as blocks and successfully evaded most of the water bandits though I did get hit a few times.

Day Two | Sam Nuea

The Lani's House by the Ponds manager had managed to get us hotel rooms in Sam Nuea, but we still hadn't worked out transportation for either of our visits in the area as well as to Vietnam. We had checked on flights from Sam Nuea to pretty much anywhere and all were booked up for the next week, so we would definitely need to go overland from Laos to Hanoi.

Lao Airlines flight attendant | arrival in Sam Nuea's newly built airport | transportation from the bus stop to our deluxe unmarked hotel | Sam Nuea

After a pretty dramatic flight into the cloud covered mountainous region we arrived at the airport which has been newly built and is about 30 kms north of Sam Nuea. After a slow bus ride we arrived in town and checked into our unmarked hotel (it is listed as Ban Tai Hotel on Google Maps. But there was no sign outside indicating the hotel's name). Al had read that it is the hotel used by Communist party dignitaries who visit Sam Nuea. On the second day, a Chinese delegation was there accompanied by attractive Laotian women hosts in matching outfits.

At the Tourist Information Office (fortunately open), Nour Amr who spoke excellent English made a call and arranged for transportation with an English speaking driver to take us to Lima Site 85.

For the rest of the day, we explored the small town of Sam Nuea and visited the market.

Scenes from Sam Nuea |

Bombs outside the hotel | open-air hair salon | chef's kids at our favorite restaurant | scenes from the main square | market sausage saleswoman | Nabra poses with a Vietnamese tourist | Sam Nuea

and some Dos and Donts in Laos: A guide to culturally sensitive travel in Lao PDR |

Tomorrow we would head to Phou Pha Thi, a sacred mountain top where the CIA had set up a radar installation site manned by deep cover US Air Force personnel called Lima Site 85 to guide American bombing missions into North Vietnam and Laos during the Secret War.

Day Three | Lima Site 85

We had an early breakfast at 7am and got on the road with our driver, Meexay for the 67 km drive to Phou Pha Thi. Very scenic drive through river valleys and up mountain ridges and past villages. Meexay who is Hmong told me all about his people and family. Though only 34 years old he has six kids, and is quite the entrepeneur with a car rental and money exchange business.

Scenes from the drive to Phou Pha Thi |

Gathering wood | Scooter-mounted shepherd herds cattle | our driver, Meexay, with exotic and apparently a edible delicacy insect | Phou Pha Thi mountain - the outcrop jutting out ontop at left is Lima Site 85 | Phou Pha Thi

On the road to Lima Site 85 with Meexay | 2 min 40 sec video | Northeastern Laos

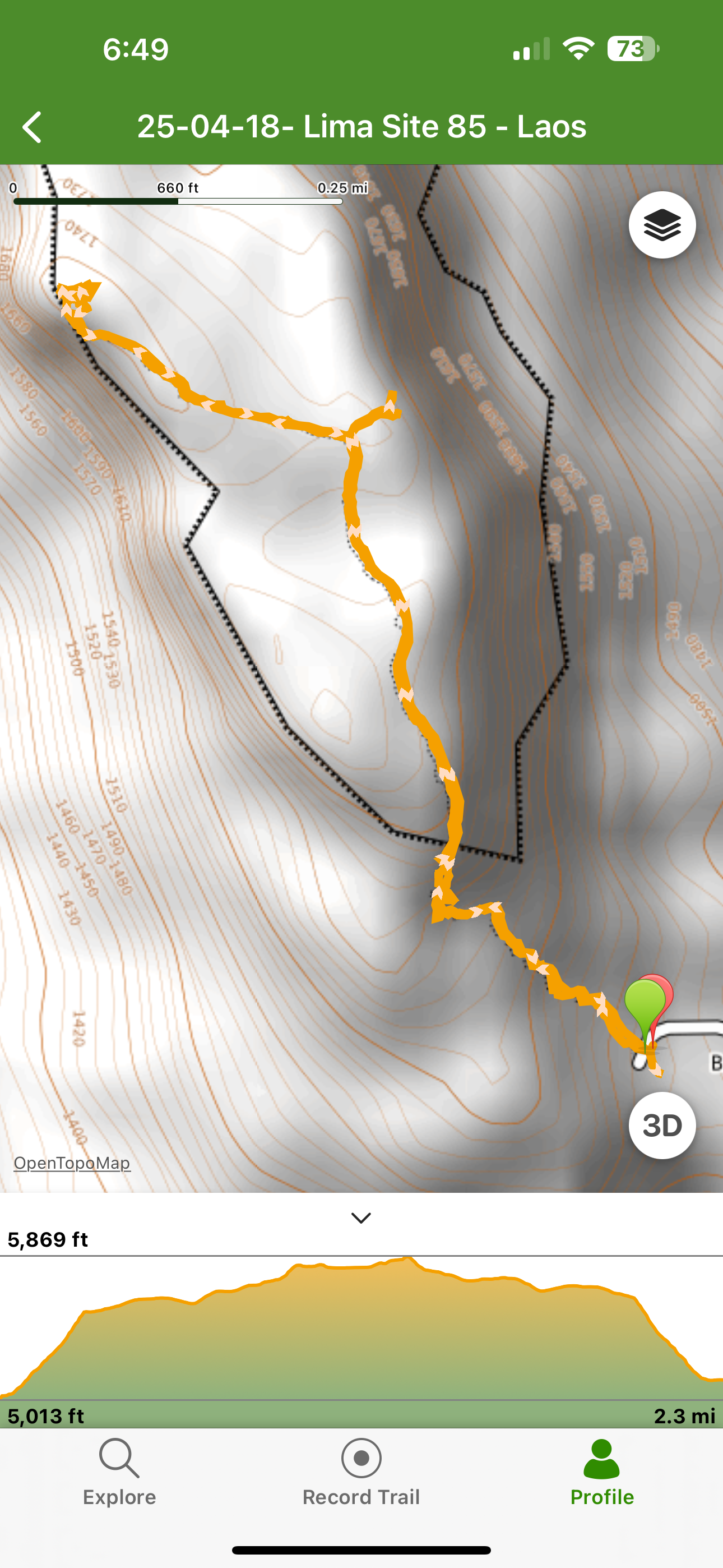

After a two hour drive, we arrived at the base of the mountain. We registered at the military outpost, paid our 50,000 kip per person fee (about 2 1/2 dollars), and consulted with the local Lao Army representative. We had packed lunches and water for the ascent to the top of the 5,800 foot mountain. Though relatively high, there was no wind at the base of the mountain as we started what would turn out to be an 860 ft elevation gain for the little over a mile hike to the summit. Fortunately, a stairway had replaced the old ladder system and though hot and humid, we made good time to the top of the plateau area. Nabra who was concerned about a high-ish altitude hike scrambled up like a mountain goat.

The hike up to Lima Site 85 |

Consulting with Lao Army commander | starting the hike | new staircase next to old ladder system | a howitzer | reaching the plateau | de-mining operation - Laos was the most heavily bomb country in the world | bamboo forest trail on way to summit | war remnants at de-mining camp | Phou Pha Thi

Hike to Lima Site 85 | Phou Pha Thi

As we made our way up to the battle site we passed numerous bomb craters and even spied some spent shells next to the trail. Laos, though not at war with the United States, was used by the North Vietnamese to transport soldiers and equipment along the Ho Chi Minh Trail into South Vietnam.

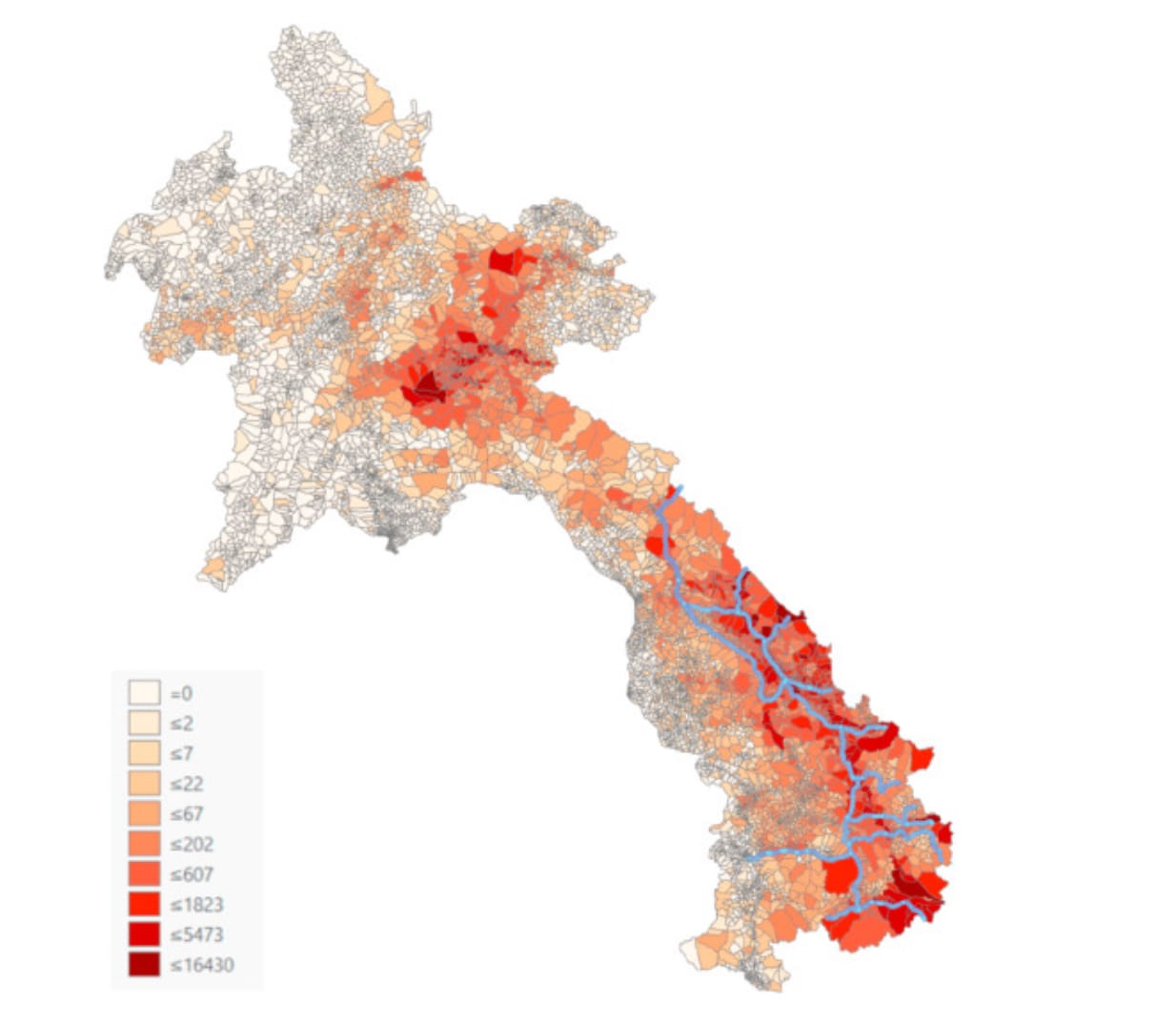

In an attempt to stop and impede the flow of weapons and soldiers, US Air Force and Navy air missions carried out an immense bombing campaign called Operation Barrel Roll in the Kingdom of Laos from 5 March 1964 to 29 March 1973.

More than 580,000 bombing sorties dropped an estimated 2.5 million tons of ordinance including 270 million cluster submunitions. More bombs were dropped over Laos than all the bombs dropped during WWII combined. Laos is the most heavily bombed country in the world and continues to suffer between 50-100 casualties yearly (many of them children who mistake them for toys) from the nearly 80 million unexploded bomblets. There have been over 50,000 civilians casualties since the war with 20,000 occurring since 1973 (the end of the bombings).

It is estimated that one bombing mission was carried out every 8 minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years over Laos.

Map of Laos showing concentration of bombings | location of Lima Site (landing site) 85, Wikilocs hiking trail app QR code | our hike to the site | Secret War era photo showing bombs and planes at a secret military base in Laos | a bomb partially concealed by vegetation along the trail | Phou Pha Thi

A brief background of the site and battle |

Lima Site 85 was one of the most critical U.S. installations in the Secret War—its radar systems perched on Phou Pha Thi guided bombing missions deep into North Vietnam. Operated under deep cover by U.S. Air Force personnel and defended by Hmong and Thai allies, the site became a prime target for North Vietnamese forces. In March 1968, after days of buildup and delayed evacuation, the mountain was overrun by a a sapper unit in a brutal assault. Most of the American personnel were killed or went missing - while others were saved in a dramatic Air America helicopter rescue - making it the largest single ground loss of Air Force members during the Vietnam War and a stark reminder of the war’s hidden costs.

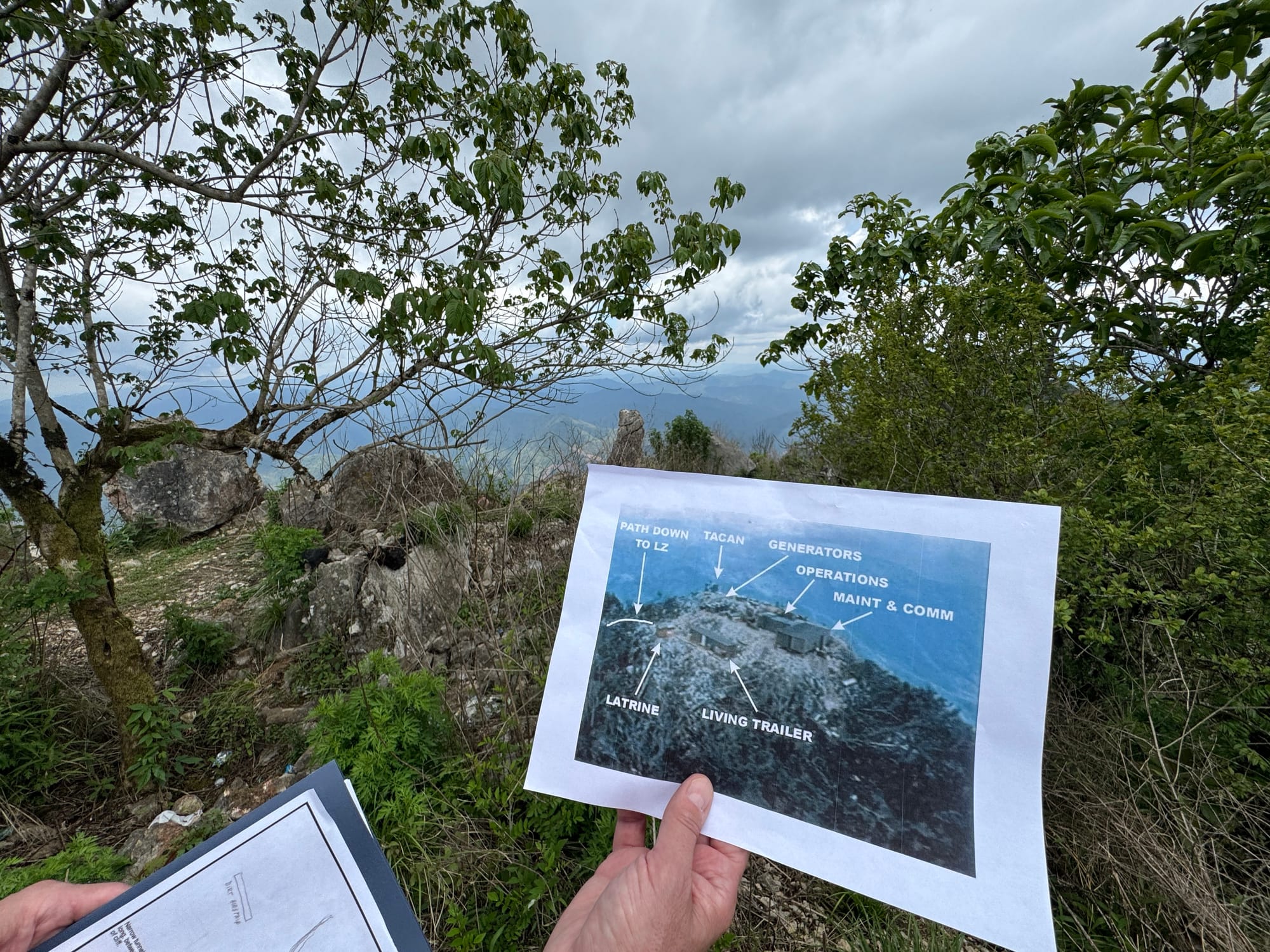

A 1967 map showing the radar and navigational compound that was manned by 19 US Air Force personnel that were "sheep-dipped" as civilian employees of the Lockheed-Martin Corporation | archival image of Lima Site 85 | Nabra and some Laotian visitors at the site | Lima Site 85

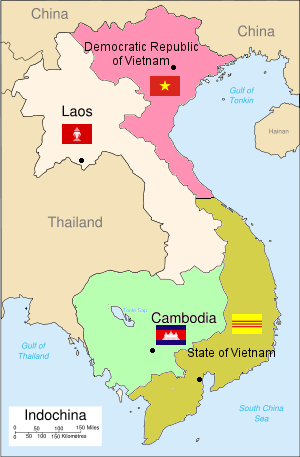

The story of Lima Site 85 is involved. As the Vietnam War expanded with the introduction of US ground troops to support the South Vietnamese government against the Viet Cong (National Liberation Army) insurgency in 1965, the North Vietnamese increased their supply and infiltration into South Vietnam via the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

The US military needed to stop that infiltration that went through Laos as well as Cambodia. With the cooperation of the Royal Lao government, supposedly a neutral country which was fighting an insurgency civil war with the North Vietnamese-supported Communist Pathet Lao forces, the CIA financed and armed the Lao tribal Hmong Clandestine Army. Along with numerous Lima Sites which usually consisted of an airfield or landing zone, the CIA supplied and advised the pro-Laotian government forces.

In order to more accurately guide American bombers on their missions in North Vietnam and along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the CIA set up the radar and navigational base Lima Site 85 on the tallest mountain closest to North Vietnam - only 15 miles away - in 1966. It was situated in the heart of communist contested Laos and only 40 miles away from the Pathet Lao headquarters at Sam Nuea - later moved to the Vieng Xay cave complex.

In 1967 with the introduction of the all-weather AN/TSQ-81 radar bombing control system, Lima Site 85 guidance accuracy increased dramatically allowing bombing missions during inclement weather and particularly during overcast and and rainy monsoon season. The system also helped decrease the number of American aircraft shot down over North Vietnam.

Though supposedly secret, the operation was well known to the North Vietnamese and knowing its importance, the Peoples Army of North Vietnam (PAVN) set in motion an elaborate plan to neutralize the base. They started to build a road south from Dien Bien Phu (the site of the French colonial army defeat in 1954) while the Pathet Lao moved towards it from their base at Sam Nuea. As an estimated 3,000 North Vietnamese soldiers closed in, an elite commando platoon from the PAVN 41st Special Forces Battalion had trained for nine months in mountain assault warfare.

The outpost was guarded by about 1,000 Hmong Army soldiers and 300 CIA-paid Thai Border Patrol soldiers. It was supplied by Air America helicopters and planes who also provided surveillance to initially un-armed American civilian Air Force technicians. As the North Vietnamese closed in on the outpost, bombing missions were redirected in an attempt to stop their advance. The important Royal Lao Army base of Nam Bac north of LS 85 was overran in January 1968.

In a unique encounter on 12 January 1968, the Vietnam People's Air Force, in one of their few operations, attempted to blow up the site with an aerial attack involving several Soviet-made Antonov An-2 biplanes that were armed with rockets and hand dropped mortars. As they made their strafing runs and dropped their bombs one aircraft was damaged by ground fire and crashed. Meanwhile, CIA officers and US controllers were able to call in an Air America Huey that pursued the remaining Antonov into North Vietnam and with a CIA operative using an AK-47 was able to shoot down the plane.

Air American hueys at the Lima Site 85 landing zone | artist depiction of the Air American helicopter attacking a Vietnamese Peoples Air Force bi-plane

As the situation became more precarious when North Vietnamese forces were able to get within artillery range and shell the position, US Ambassador to Laos William Sullivan who was also in charge of the CIA Secret War operation prepared for the evacuation of the Americans and their Hmong and Thai allies.

Meanwhile in South Vietnam, the Tet Offensive which had started on 30 January 1968 was still in progress with the seige of Khe Sanh continuing and other engagement throughout the south. Orders were given, possibly even from the White House according to some sources, to hold out at Lima Site 85 and keep the substantial enemies forces at bay for as long as possible.

With the likelihood of outpost being overrun as North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces closed in, Ambassador Sullivan finally ordered the evacuation of the site to begin at first light on 10 March 1968. In defiance of the Ambassador's orders not to arm the "civilians", Major Richard Secord, had earlier provided the 19 outpost personnel with M-16s and some grenades.

Lima Site 85 | 3 min video | Phou Pha Thi

With regular North Vietnamese forces engaging the Hmong and Thai security forces protecting the outpost, the 33-man NVA Special Forces platoon divided into five cells climbed the cliffs -avoiding detection- and were in position to attack at 3am.

The resulting ambush of the attack left 11 Americans MIA or KIA and 42 Hmong and Thai soldiers dead.

As the battle between the NVA commandos and lightly armed US personnel raged, a CIA operative at the helicopter landing zone called in air support and evacuation helicopters and then rushed up to engage the attackers.

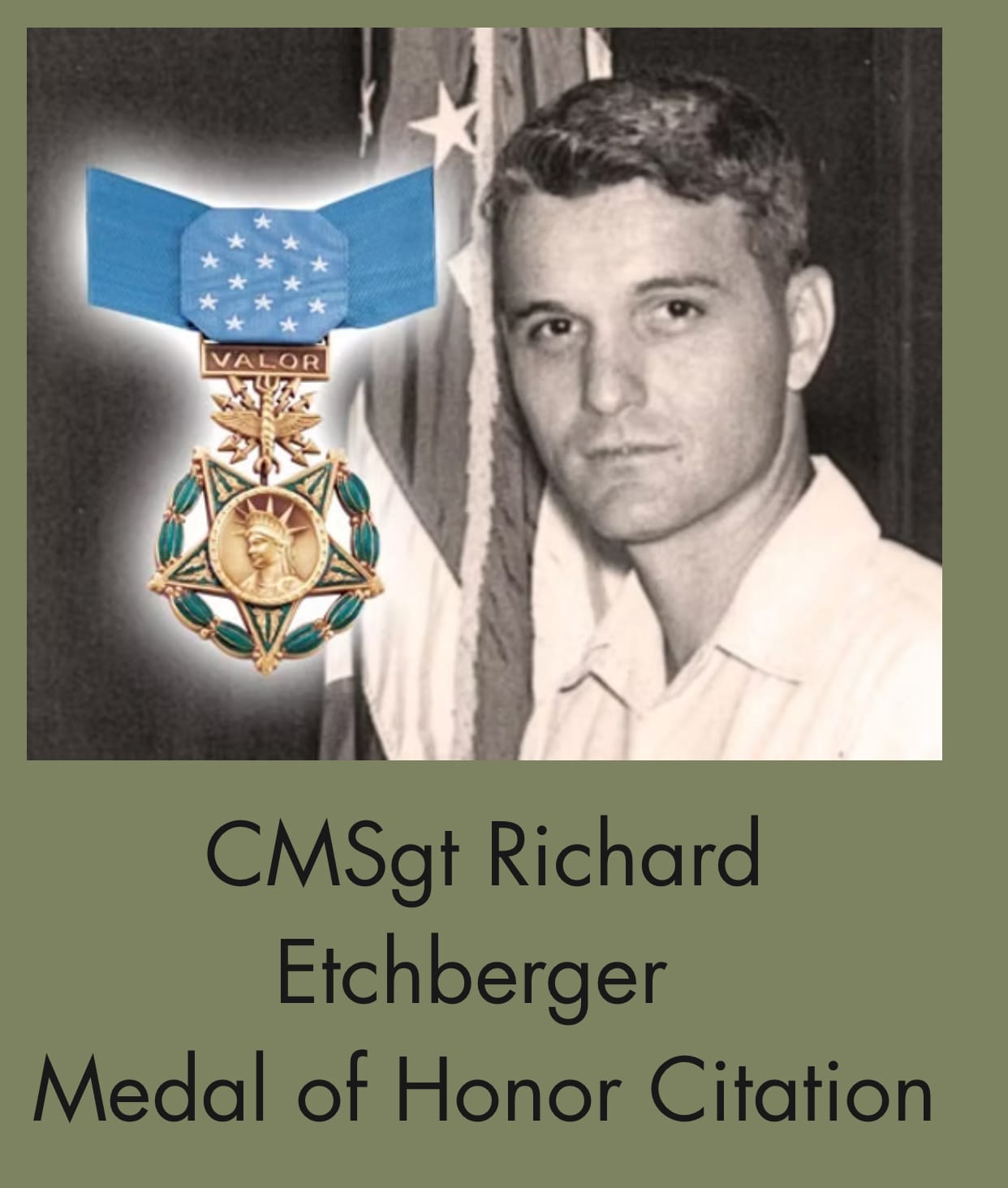

Medal of Honor recipient Chief Master Sargeant Richard Etchberger | the patch of the Air Force personnel who operated Lima Site 85 | photos courtesy of Limasite85.com

On a ledge below the cliff, CMSGT Etchberger held off sappers in a prolonged fight, eventually helping get surviving fellow airmen lifted onto an Air America helicopter hovering precariously over their position.

Etchberger was initially awarded the Air Force Cross, but in 2010 his award was upgrade to the Medal of Honor.

The Medal of Honor citation |

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, March 3, 1863, has awarded, in the name of The Congress, the Medal of Honor to Chief Master Sergeant Richard L. Etchberger, United States Air Force, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty.

Chief Master Sergeant Richard L. Etchberger distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism on March 11, 1968, in the country of Laos, while assigned a Ground Radar Superintendent, Detachment 1, 1043d Radar Evaluation Squadron.

On that day, Chief Etchberger and his team of technicians were manning a top-secret defensive position at Lima Site 85 when the base was overrun by an enemy ground force. Receiving sustained and withering heavy artillery attacks directly upon his unit’s position, Chief Etchberger’s entire crew lay dead or severely wounded. Despite having received little or no combat training, Chief Etchberger single-handedly held off the enemy with an M-16, while simultaneously directing air strikes into the area and calling for air rescue. Because of his fierce defense and heroic and selfless actions, he was able to deny the enemy access to his position and save the lives of his remaining crew. With the arrival of the rescue aircraft, Chief Etchberger, without hesitation, repeatedly and deliberately risked his own life, exposing himself to heavy enemy fire in order to place three surviving wounded comrades into rescue slings hanging from the hovering helicopter waiting to airlift them to safety. With his remaining crew safely aboard, Chief Etchberger finally climbed into an evacuation sling himself, only to be fatally wounded by enemy ground fire as he was being raised into the aircraft.

Chief Etchberger’s bravery and determination in the face of persistent enemy fire and overwhelming odds are in keeping with the highest standards of performance and traditions of military service. Chief Etchberger’s gallantry, self-sacrifice, and profound concern for his fellow men at risk of his life, above and beyond the call of duty, reflect the highest credit upon himself and the United States Air Force.

Nabra and Al on a ledge outside a cave near where the valiant efforts of US Air Force Chief Master Sargeant Richard L. Etchberger is credit with saving several servicemen lives before he was fatally shot | Al and I | photo contribution by Nabra Nelson

Of the 11 Americans killed, other than Chief Etchberger, only three other servicemen's remains have been found and identified. After visits by US Department of Defense Joint POW/MIA Accounting Agency in 2024, Sgt David S Price was the latest MIA to have had remains recovered.

Exploring the remote site with it's exposed steep drop offs and exposed terrain, it gives you a clear sense of just how vulnerable the defenders were. There’s not much left—some battle effects, rusted metal, and stark terrain—but being there gives you a sense of the battle in a way no written account can.

For more information on the Battle of Lima Site 85, you can visit the following sites: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Lima_Site_85 and https://www.limasite85.com/

We headed down the mountain, stopping at the landing zone where we found the artillery gun that had been knocked out commission by the North Vietnamese.

Artillery piece | LZ (landing zone) as seen from the outpost | Lima Site 85

On the way back, smoke from slash and burn agriculture obscured the mountains and strong winds brought short downpours of rain. We briefly stopped at a Buddha Cave shrine as dark clouds and an impending storm darkened the sky after an impactful and unforgettable day.

The Buddha Cave Shrine and its monkey deity guardian | Ban ThamPaThe

We ended the day with an excellent pizza at Pizza Aloha. We were the only diners at the one table outdoor eatery as a gentle rain fell and thunder rumbled in the distance.

Day Four | Pathet Lao and the Vieng Xay cave complex

We were up early and on the road to Vieng Xay, a natural karst and cavern geological formation, where the Communist insurgency army Pathet Lao had moved their headquarters to shelter against American bombing raids in 1964.

Initially the non-communist revolutionary movement was formed in 1945 and in 1950 Prince Souphanouvong of the Royal Lao family, who had lived in Vietnam and met Ho Chi Minh, became it's leader. The renamed Pathet Lao joined with the Viet Minh to fight against the French colonialist rulers in the First Indochina War. In 1953 the now communist revolutionary force was joined by Viet Minh insurgents and invaded Laos and established a base of operation in Vieng Xay with close collaboration with the Viet Minh.

In 1954 after a number of French colonial Army defeats in Vietnam by the Viet Minh, most notably at Dien Bien Phu, the Geneva Conference divided French Indochina into four countries, Democratic Republic of Vietnam and State of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. All foreign forces were to be withdrawn, but the North Vietnamese forces remained along the border regions of Laos and continued to coordinate the Pathet Lao Civil War in Laos.

The 1954 partition of Indochina into four countries | Prince Souphanouvong - Pathet Lao leader and half brother to the ruling family of the Kingdom of Lao | Pathet Lao soldiers 1953

In 1960s, with the United States becoming increasingly involved with military and political support for the South Vietnamese government and fear of the spread of communism, the US backed the Kingdom of Laos. It started to supply weapons and training to the Royal Lao Army as well as the CIA recruited Hmong clandestine guerrilla army led by Major General Vang Pao.

We arrived at the Vieng Xay ticket office by 8:30am and needed to wait awhile until a guide could be found. With our audio tour headsets, our guide Goa led us to the sites on his Vespa while we followed behind in a car. There are over 500 caverns and caves that were used by the Pathet Lao and with the local population the caves housed up to 23,000 people.

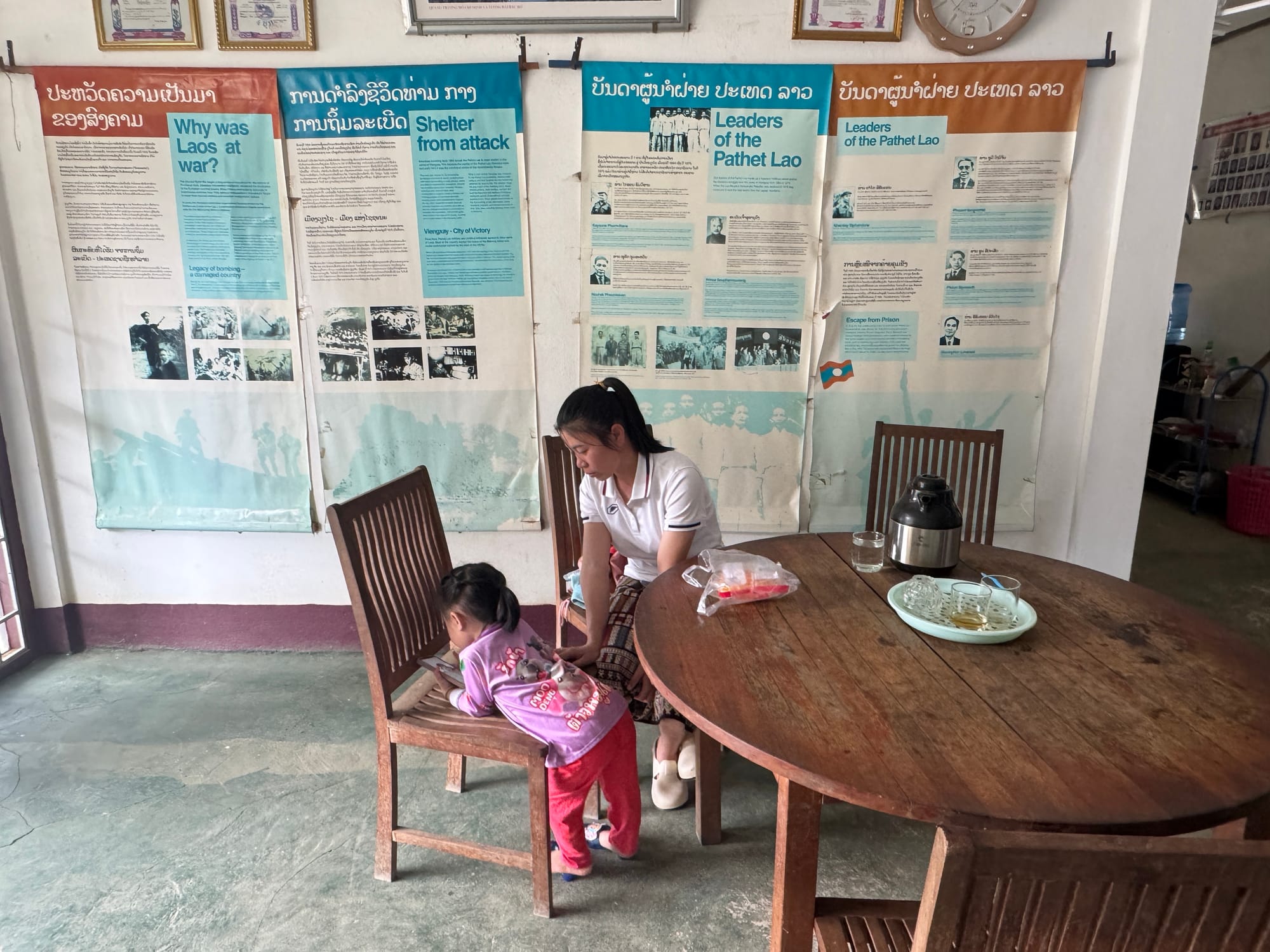

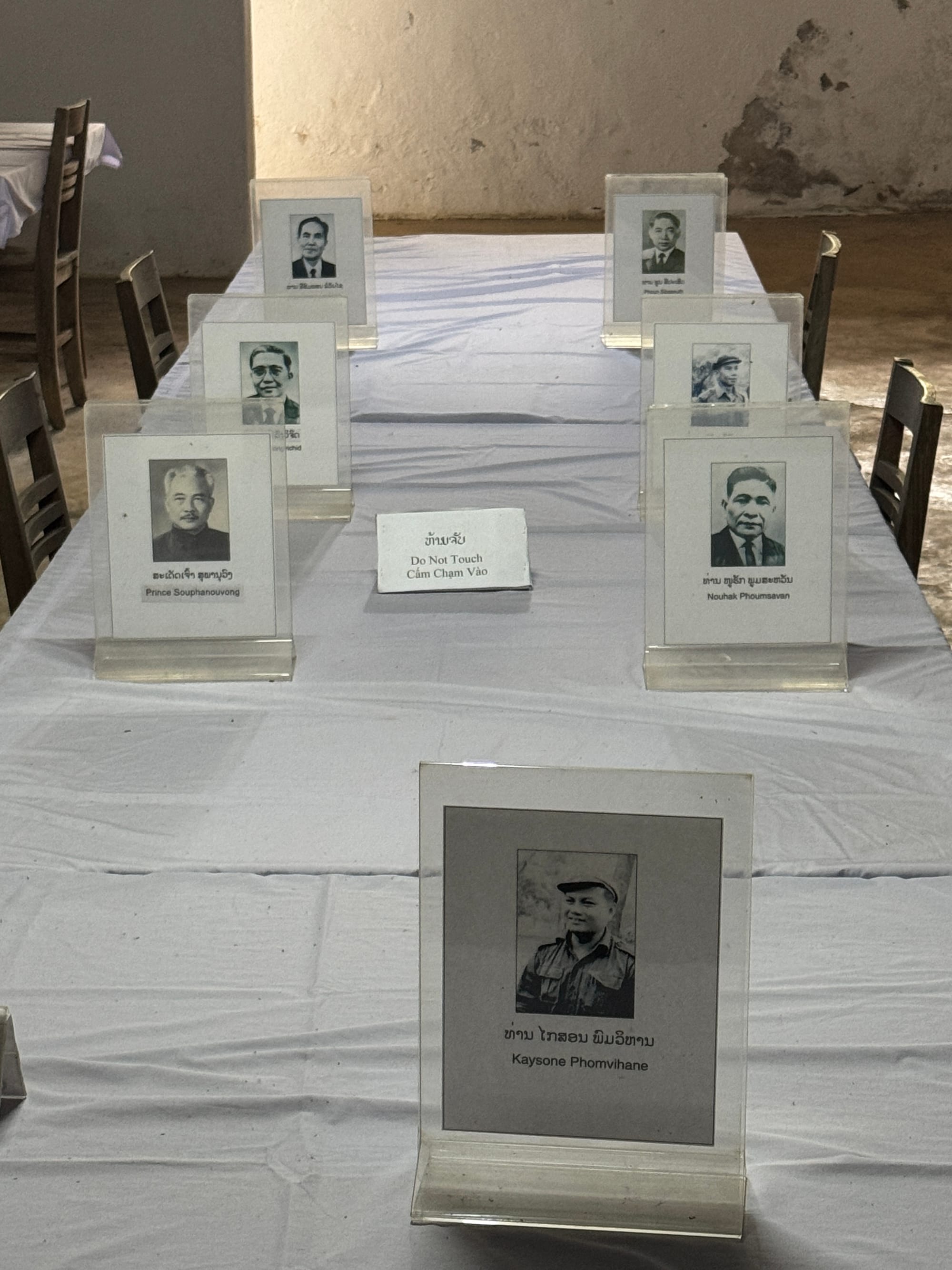

A map showing the Pathet Lao insurgency against the Kingdom of Laos | a museum employee and her daughter | Pathet Lao leadership in the 1960s | a dish with the leaders of Laos, Cambodia, People Republic of Vietnam and the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) | Vieng Xay

A little more background information on the the Pathet Lao and Vieng Xay |

East of Sam Nuea, we visited Vieng Xay, a quiet mountain town which played a major role in the Secret War in Laos. This remote area was the cave stronghold of the Pathet Lao, the communist movement that fought against the U.S.-backed royal Lao government with strong support from the North Vietnamese Army.

The Pathet Lao cave network evolved underneath the karst hills that are throughout the area. These expanded natural shelters actually became a hidden city: the Pathet Lao and their supporters built underground homes, meeting rooms, schools, a hospital, even a theater hall, inside the rock tunnels. For nearly a decade, while under regular bombardment, the Pathet Lao leadership directed their war effort from here. It is now a nationalist monument to the Pathet Lao revolution.

The Vieng Xay Cave Complex visit and photos |

The first cave complex we visited was that of the Kaysone Phomvihane, leader of the Communist Lao People's Revolutionary Party and first president of the Lao Democratic People's Republic. This cave complex also housed his family and was where the Politburo and the leadership met.

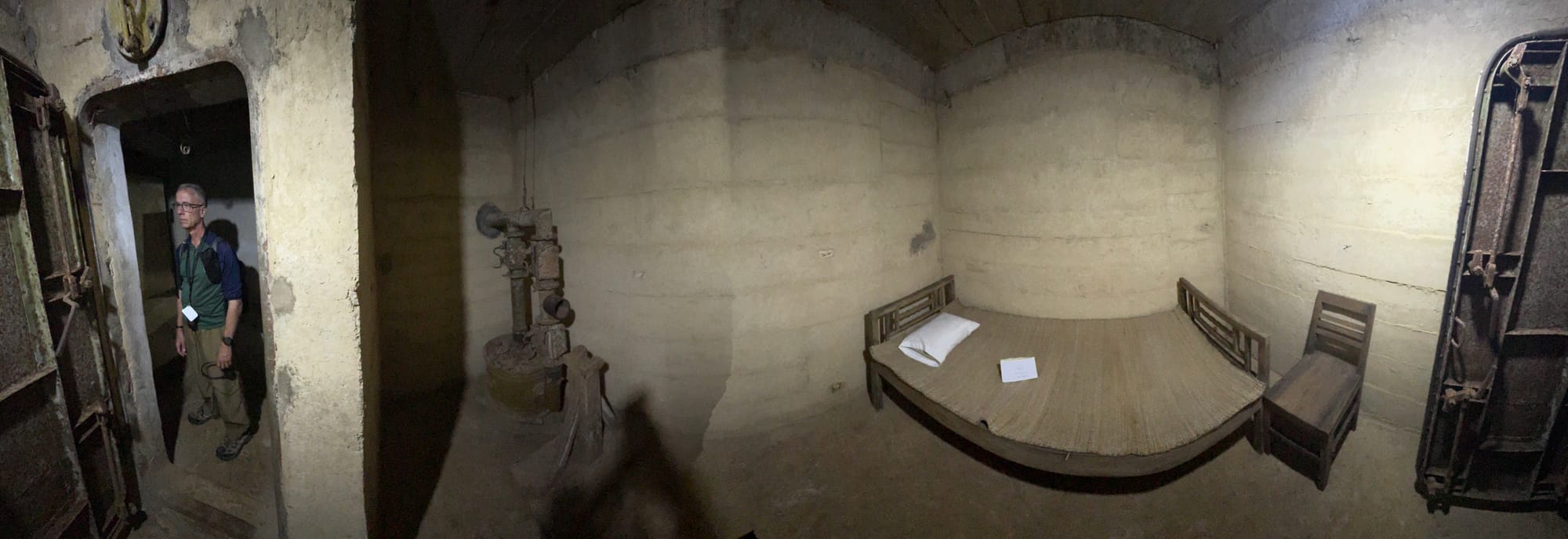

Secretaries Cave | geological formation | air tight chamber with own oxygen supply in case of gas attack | Politburo meeting room | the leader's bedroom

The Pathet Lao, in this remote and jungle covered mountainous region of Laos near the North Vietnamese border, were not in danger of any ground offensive but had to protect themselves and the villages from the intense Ambombing campaign called Barrel Roll.

Working primarily at night they expanded and reinforced the caverns by carving tunnels, widening caves, building rooms including specially air sealed ones with their own oxygen supply in case of gas attacks.

Bomb crater |

Former Pathet Lao headquarter | Vieng Xay Caves | 1 minute video

The karst and cavern geographical setting is spectacular with its giant limestone towers covered in jungle foliage. With assistance from a number of international organizations from the Netherlands, Japan and the United Nations, the Laos government hopes to create a tourist site as this unusual site offers the opportunity to explore a largely intact revolutionary base.

Prince Souphanouvong cave complex |

Prince Souphanouvong cave complex | bomb craters converted into a swimming pool and now pond | memorial to his son who was killed in the Lao CIvil War | kitchen | his daughter's room | exterior of the caves with blast walls |

Our visit there was kind of surreal— while trekking through the cool, quiet tunnels, we tried to imagine what it must have been like back in the day planning and fighting an underground revolution, coming out only at night to breathe fresh air, farm, take care of personal affairs and to run the operations in support of the war. We also tried to imagine US planes overhead, the bombings, and the challenges downed aviators had if they had to bailout in the surrounding Laotian jungle.

Blast wall at entrance to a huge underground cavern where large gatherings were held | tunnels to other caverns in the underground city

Almost all outdoor activity during the nine year US bombing campaign (1964-1973) took place during the night. Harvesting of fields, tending to the herds and collecting wood was done under torch light in the evenings. Any movement or something that stood out was bombed. Even light colored animals that could be spotted from the air were done away with. Though relatively well protected from the actual bomb explosions, smoke from burning brush and falling rocks from strikes on the karst hills were daily dangers.

Anti-aircraft position | more caves and their blast walls | caverns with stalactites

Cavern where large gatherings and theater productions where held | an image from a play featuring Pathet Lao soldiers | Laotian children and a blast wall | tour group - inspired by Nabra dancing on the stage - sings a local tune

Other than a group of women Laotian visitors and a family, we were the only other visitors that we saw during our three-hour tour. We joked around a bit to the great amusement of our guide, Choa, and did some group photos together.

Fun photos from the day |

Nabra selfie with children | Al and I joking in the toilet | Nabra dances across the stage | posing with other visitors | our guide Choa with a souvenir Al gave to him

Day Five | Good bye Laos

After an amazing and too short five day visit to Laos, we were heading overland to Hanoi where we would be joined by friends Mike Bayles and Bill Adams for the Vietnam portion of the adventure.

We had been invited by Meexay to have a Hmong lunch with his family at their home near one of the border crossings into Vietnam. However, after he checked with local border contacts he learned that our visas to Vietnam only permitted us to enter the country via the Ban Na Meo border crossing.

He arranged for a Vietnamese driver and transport to meet us on the other side and take us to Hanoi.

Scenes from the 83 kms, 2 hour drive from Sam Nuea to Ban Na Meo |

On the road to Vietnam | snaps from the car | Northwestern Laos

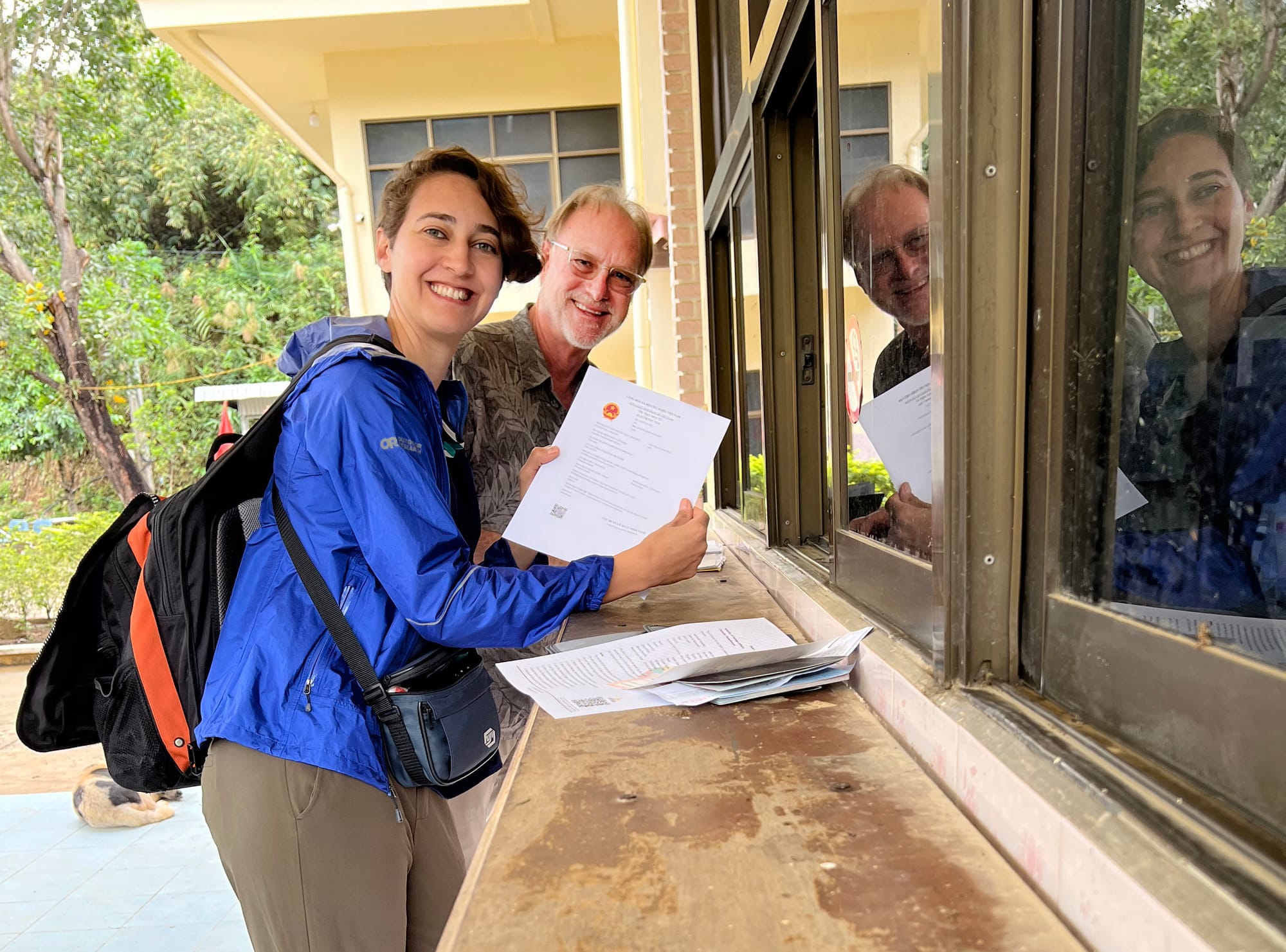

At the Ban Na Meo border | communicating with Meexay | showing our Vietnam visas | Ban Na Meo

We had hoped to spend the rest of our Lao Kip at the border, but other than the nice looking border station there was not much there.

No border traffic going in either direction. It was very quiet and after having our papers checked and passports stamped we proceeded by foot to cross over the Nam Soi River and into Vietnam.

We were sad to say "Sabaidi" (Good bye) to Laos. It had been an amazing adventure and our interactions with the Lao people had been wonderful. At every turn they had been so hospitable, friendly and full of great spirit and hope. Bee Ma Lao (Lao New Year) had been a trip. Strange places like the Buddha Park, the CIA Secret War history and the revolutionary base deep in the mountainous jungle were unique experiences that whetted our appetite to return one day to this special place.

We had had a taste of this fascinating country and its people - and though we were sad to leave, we were looking forward to new adventures at our next destination.

Nabra and I, in "No Man's Land", make the 350 meter walk over the Sam Noi RIver to Vietnam | photo by Al Willner